Reeds and Resilience: The Wetland Filtering a Town’s Wastewater Naturally

By Merrin Brooks

At the edge of the town, where houses thin out, and hedgerows begin to stitch the land back together, water slows. The road bends away. The air changes. Reeds rise in soft ranks, their feathery heads catching the light. From a distance, this place reads as nature reclaiming space. Few would guess that beneath the reeds, an entire town’s wastewater is being quietly treated.

There are no chimneys here. No turbines or control panels. No warning signs about industrial hazards. What stands instead is a living system, designed with care and restraint, where plants, microbes and gravity perform the work that elsewhere depends on concrete, chemicals and continuous electricity.

This reed bed does not supplement a treatment works. It is the treatment works.

A system built on patience

Wastewater enters the wetland gently, dispersed across a series of shallow basins. The design encourages slowness. Water spreads rather than rushes, guided through gravel beds densely planted with common reed. What follows is not a single process but a layered one, unfolding over time.

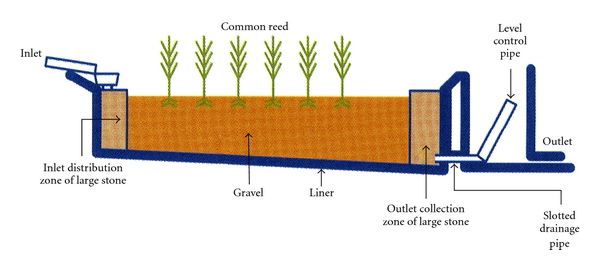

Simplified layout of a tertiary treatment reed-bed shown is the simplified layout of a tertiary treatment reed-bed is shown, where wastewater enters at the inlet, is cleaned in the reed-bed area through filtration and absorption of nutrients by the reeds, and released at the outlet into rivers and streams, hence the location of the reed-bed alongside flowing water. Source is Severn Trent Water

Below the surface, reed roots form an underground architecture. Their fine filaments provide vast surface area for microbial life, the unseen workforce of water treatment. Aerobic bacteria thrive where oxygen travels down the reed stems. Anaerobic microbes work deeper in the substrate. Together they break down organic matter, reduce nutrients, and neutralise pathogens.

Solids settle. Phosphates bind to mineral surfaces. Nitrogen is transformed and released harmlessly into the atmosphere. By the time the water emerges at the far end of the system, it is clear, stable and ready to rejoin the natural water cycle.

Nothing is hurried. Nothing is forced. The system works because it is allowed to take its time.

Engineering that listens to ecology

Constructed wetlands are often described as nature-based solutions, but that phrase can disguise the precision involved. This is not simply letting a marsh grow and hoping for the best. It is careful ecological engineering, informed by hydrology, soil science and decades of field evidence.

Flow rates are calculated. Bed depths are tuned. Plant densities are chosen to balance filtration and oxygen transfer. Seasonal variations are anticipated rather than resisted. The wetland is designed to cope with daily sewage loads, storm surges, summer droughts and winter cold, all without external power.

In conventional treatment plants, resilience is built through redundancy. Backup pumps, generators and chemical stores stand ready for failure. Here, resilience is embedded in the system itself. If one reed dies, another grows. If flows increase, water spreads and slows. If power fails, nothing stops.

From hidden utility to shared place

Most towns learn to live with their wastewater infrastructure by pretending it is not there. Plants are fenced off, buffered with trees, pushed to the margins. This wetland has taken a different path.

Footpaths trace its edges. Benches overlook the water. Information boards explain how sewage becomes clean water through biological processes rather than industrial ones. Schools visit. Birdwatchers linger. What was once a necessary inconvenience has become a place of curiosity and pride.

The ecological benefits are immediate and visible. Birds nest among the reeds. Frogs and newts return to shallow pools. Insects swarm and feed. The wetland becomes a stepping stone for biodiversity in an otherwise managed landscape.

Infrastructure here does not displace nature. It hosts it.

Energy, cost and climate resilience

Wastewater treatment is one of the quiet energy drains of modern life. Pumps lift water. Aerators churn it. Blowers force oxygen into tanks around the clock. As energy prices rise and climate targets tighten, these systems become increasingly expensive to run and difficult to defend.

An energy free reed bed offers a fundamentally different economic story. Capital costs are often comparable to conventional plants, particularly where land is available. Operational costs, however, are dramatically lower. There are no electricity bills tied to treatment performance. Maintenance focuses on vegetation management rather than mechanical repair.

The climate benefits follow naturally. Carbon emissions are reduced at source. The system remains operational during power outages. During heavy rainfall, the wetland can absorb and temporarily store water, easing pressure on downstream rivers and reducing overflow risk.

In a future defined by extremes, this kind of flexibility is not a luxury. It is essential.

Limits, honesty and place

Reed beds are not a universal answer. They require space. They work best where land values allow for generosity. In dense urban settings, vertical and mechanical systems will continue to play a role. Cold climates demand careful design to maintain year round performance.

What matters is not replacing every treatment plant with reeds, but recognising where this approach makes sense and having the confidence to use it at meaningful scale.

Too often, nature based systems are relegated to pilots and demonstrations, treated as interesting but peripheral. This wetland challenges that assumption. It proves that living systems can handle core civic functions reliably, affordably and visibly.

A different idea of progress

Standing beside the wetland, it is easy to forget what it is doing. The water moves quietly. The reeds whisper. A heron lifts itself into the air. Progress here does not announce itself with noise or steel.

Yet every household in the town is connected to this place. Every flush, every drain, every drop of used water passes through roots and microbes before returning clean to the wider environment.

There is something quietly radical in that idea. That the most essential systems of modern life might be softened rather than hardened. That infrastructure could heal landscapes instead of scarring them. That resilience might come from working with natural processes rather than overpowering them.

In an age fascinated by speed and scale, this wetland offers another vision. One where the future of water arrives slowly, takes root, and begins to sway.