For decades, urban expansion in the UK has often come at the expense of nature. Habitats paved over, wetlands drained, watercourses boxed into culverts, all in the name of growth. But times are changing. With Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) now a legal requirement for most developments in England, developers are being asked to build not just greener places, but wilder, wetter ones too.

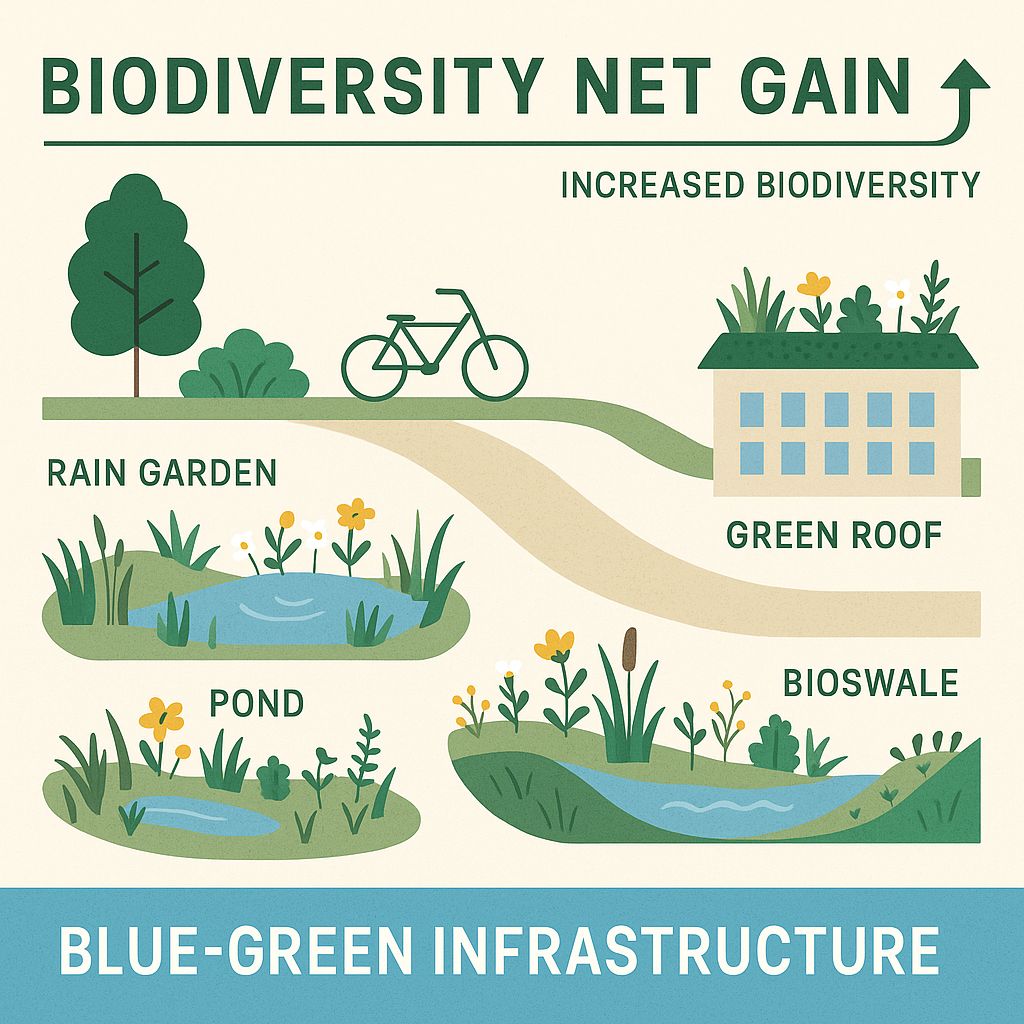

Water, once seen mainly as a drainage problem, is emerging as a vital part of the solution. Sustainable drainage systems, rain gardens, wetland habitats and restored streams are increasingly being used not just to manage runoff, but to restore biodiversity and create attractive, resilient places to live and work.

It’s a green and blue opportunity. But to seize it, the construction industry must rethink how water is designed, managed, and valued on every site.

What is Biodiversity Net Gain, and Why Now?

BNG is a planning policy that requires developers in England to ensure their projects leave the natural environment in a measurably better state than before. Since February 2024, it has been mandatory for most major developments under the Environment Act 2021.

The requirement is simple on paper: achieve a minimum 10% net gain in biodiversity units, measured using a government-approved metric. These units are based on habitat type, condition and distinctiveness. But delivering that gain in practice, particularly on-site, requires careful planning, smart design, and early-stage ecological input.

While some developers may meet the target through off-site habitat creation or credits, planning authorities increasingly prefer gains to be made on or near the development site itself. This is where water comes in.

Why Water is a Biodiversity Powerhouse

Wet habitats punch well above their weight in terms of ecological value. Ponds, swales, wetlands and ditches provide breeding grounds for amphibians, feeding areas for birds, and refuge for insects, bats and other wildlife. Even small features can become biodiversity hotspots when designed with care.

The Natural England Green Infrastructure Framework recognises the value of blue infrastructure, noting that water features can contribute significantly to BNG scores, carbon capture, climate adaptation and public wellbeing, a rare convergence of goals.

Crucially, many water-based features can serve dual purposes:

A swale that slows runoff and hosts wildflowers

A detention basin that doubles as amphibian habitat

A rain garden that filters water and feeds pollinators

Rather than treating water management and biodiversity as separate disciplines, the most progressive projects integrate the two from the outset.

Designing for Dual Purpose

To align water design with BNG objectives, developers and design teams should focus on three principles: naturalise, diversify, and connect.

1. Naturalise:

Avoid concrete-lined or artificially straightened water features. Use gently sloping banks, native planting and varied depths to mimic natural conditions. This supports habitat complexity and helps BNG assessments score higher for condition.

2. Diversify:

Incorporate a range of wet and damp habitat types, ponds, scrapes, wet meadows, and reedbeds. Diversity supports a wider array of species and adds resilience to climate impacts such as drought or flash flooding.

3. Connect:

Create ecological corridors by linking water features with green roofs, hedgerows, and woodland planting. Connectivity allows species to move through the landscape, find breeding grounds, and maintain viable populations.

SuDS: From Drainage Tool to Nature-Based Solution

Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) are no longer just about managing stormwater. The latest guidance from CIRIA (The SuDS Manual C753) encourages developers to see SuDS as multi-functional assets, improving water quality, enhancing biodiversity, and creating attractive public spaces.

Features such as:

Wet swales planted with sedges and rushes

Basins with permanent pools and seasonal margins

Rain gardens that soak up runoff and support wildflowers

Green roofs that slow water and boost pollinators

...can all contribute to BNG if designed with ecology in mind.

Challenges on the Ground

Integrating water for biodiversity isn’t without its challenges. Space is often cited as a constraint, particularly on urban brownfield sites. There's also a risk of tension between engineers (focused on hydraulic performance) and ecologists (focused on habitat quality).

To address this, many successful schemes are now adopting multi-disciplinary early-stage design, bringing engineers, ecologists, landscape architects and planners together before layouts are fixed.

There’s also a learning curve. While some planning teams and developers are well-versed in BNG, others are still catching up, and unclear on how water design fits into the equation. This underlines the need for upskilling and clearer case studies across the industry.

Leading by Example

Several developments have already shown what’s possible:

Upton, Northampton – A benchmark SuDS-led housing development where open swales, basins and wetlands have boosted biodiversity and public amenity.

Trumpington Meadows, Cambridge – Uses restored river channels and wetland margins to support protected species including water voles and dragonflies.

Kingsbrook, Aylesbury – A Barratt Homes scheme developed in partnership with the RSPB, featuring wildlife ponds, wet meadows and nesting areas integrated throughout the housing layout.

These projects demonstrate that water-sensitive design need not be at odds with commercial delivery, and can, in fact, enhance placemaking, sales value and community appeal.

A New Standard for Development?

With climate pressures rising and nature in decline, the construction industry is being called to act as steward as well as builder. Water — so often treated as a risk to mitigate and can become a cornerstone of that stewardship.

When rain doesn’t just run off but feeds a wildflower-dotted pond…

When a drainage ditch becomes a home for frogs and dragonflies…

When stormwater becomes habitat rather than hazard…

…we begin to build differently.

By embedding blue infrastructure into the DNA of new developments, the sector can meet legal requirements, unlock planning value, and restore nature, site by site.